The New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt

The New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570–1069 BCE) was the most powerful and prosperous era in ancient Egyptian history. Following the turmoil of the Second Intermediate Period, Egypt emerged as a true empire, ruled by pharaohs whose authority extended across Nubia and deep into the Near East. This "Empire Age," covering the 18th, 19th, and early 20th Dynasties, marked the height of Egypt’s wealth, military power, and cultural influence. Monumental temples such as Abu Simbel, Luxor, and Abydos reflect the artistic brilliance of the age, while Thebes became a thriving religious center. The New Kingdom’s political stability and grand achievements left a legacy that continues to captivate historians and readers today.

The Rise of the New Kingdom of Egypt

Ancient Egypt's political map changed dramatically around 1782 BCE. The Middle Kingdom collapsed, and foreign powers took control. The Hyksos, who came from West Asia, grabbed power in Lower Egypt. Meanwhile, the Kingdom of Kush rose in the south. This split in power marked the Second Intermediate Period and set the stage for Egypt's most powerful era.

The fall of the Hyksos and reunification under Ahmose I

The clash with the Hyksos started when Egyptian king Seqenenra Tao saw a message from Hyksos king Apepi as a challenge. Tao died in battle, and his son Kamose picked up the fight. Kamose claimed he beat the Hyksos after attacking Avaris. Historical evidence tells us that Avaris stayed under Hyksos control until Ahmose I ruled (c. 1539-1514 BCE).

Ahmose I, Kamose's brother, finally drove out the Hyksos through a decisive military campaign. He first captured Memphis, Egypt's traditional capital. He then launched a water attack against Avaris and followed it with a land siege. After taking Avaris, Ahmose chased the Hyksos to Sharuhen in Palestine. The city fell after a three-year siege. This victory ended foreign rule in Egypt and kicked off the New Kingdom period.

Establishing buffer zones and military reforms

Ahmose I created buffer zones around Egypt to stop future invasions. He made Egypt's borders secure by launching military campaigns in Nubia to the south and pushing into Canaan and Syria to the northeast. He brought Nubia back under Egyptian rule and built a new administrative center at Buhen.

The military changed completely during this time. New Kingdom armies had full-time soldiers working together on a state level for the first time in Egyptian history. Egyptians took the Hyksos' military innovations and made them better. They improved the chariot, composite bow, and bronze weapons. These advances helped Egypt face powerful Near Eastern kingdoms in the years that followed.

The role of Thebes as a political and religious center

Thebes became Egypt's capital under Ahmose's rule. People called the city by its sacred name P-Amen or Pa-Amen, which meant "the abode of Amen". The temple complex at Karnak grew in importance, while the old Ra cult in Heliopolis became less significant. Several stone slabs found at Karnak show Ahmose's contributions to the temple and paint him as a generous supporter.

Ahmose I's reunification of Egypt brought new life to royal art and monument building. This cultural revival, combined with military might and expanding territory, laid the groundwork for Egypt's golden age.

The 18th Dynasty: Expansion, Innovation, and Reform

The Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt marked a golden era from 1550/1549 to 1292 BC. This period brought remarkable territorial growth and cultural achievements during the New Kingdom. Several powerful rulers helped Egypt become an international superpower with an empire reaching from Syria to Upper Nubia.

Hatshepsut's trade expeditions and building projects

Queen Hatshepsut ruled for over twenty years (c. 1479-1458 BC), making her the longest-serving woman pharaoh from an indigenous Egyptian dynasty. She chose economic growth over military conquest and rebuilt trade networks that had fallen apart during the Hyksos occupation. Her famous expedition to the Land of Punt brought back 31 live myrrh trees, frankincense, and other luxury items. She became the first to use charred frankincense as kohl eyeliner—a groundbreaking use of this resin.

Hatshepsut's building legacy stands among Egypt's most impressive. She ordered hundreds of construction projects throughout Upper and Lower Egypt. Her architectural achievements were remarkable:

- She restored the Precinct of Mut at Karnak

- She built twin obelisks at Karnak Temple's entrance (world's tallest at that time)

- She created the Temple of Pakhet at Beni Hasan

- She built her masterpiece, the Djeser-Djeseru ("the Holy of Holies") at Deir el-Bahari

Thutmose III and the creation of the Egyptian Empire

Thutmose III emerged as Egypt's greatest military pharaoh after Hatshepsut died. He led 17 to 20 successful campaigns. Historian Richard A. Gabriel called him the "Napoleon of Egypt". His conquests helped Egypt grow into an empire that stretched from the Euphrates to Nubia.

He made history by creating Egypt's first navy. His victory at the Battle of Megiddo (May 9, 1457 BC) gave him control of northern Canaan. Assyrian, Babylonian, and Hittite kings paid him tribute throughout his reign.

Amenhotep III and the golden age of diplomacy

Amenhotep III's reign (c. 1388-1351 BC) brought unmatched prosperity and international influence. The Amarna Letters show his diplomatic skills through correspondence with rulers of Assyria, Mitanni, Babylon, and Hatti. He kept Egypt's position as the ancient Near East's leading power through mutually beneficial alliances and gift exchanges.

People called him "Amenhotep the Magnificent." He commissioned more than 250 statues—more than any other pharaoh—and celebrated three Sed festivals. Only Ramesses II's much longer reign could match his extensive building program.

Akhenaten's religious revolution and the Amarna Period

Akhenaten (c. 1353-1336 BC) reshaped Egyptian religion. He elevated the sun disk Aten from being the most prominent deity to becoming the only god. He built a new capital called Akhetaten (modern Amarna).

This religious change brought revolutionary artistic styles. Artists showed the royal family with elongated heads, thin limbs, and stomach paunches—completely different from traditional Egyptian art. These changes let Akhenaten become the only connection between people and the Aten.

Tutankhamun and the restoration of tradition

Tutankhamun became pharaoh at age nine and inherited the chaos from Akhenaten's religious revolution. His reign brought one of Egypt's greatest restorations. The Restoration Stela from Year 4 of his reign described the Amarna Period as disastrous.

He quickly ended his father's radical monotheistic vision. He brought back the traditional gods and moved the capital from Amarna to Memphis. The young pharaoh supported important religious cults, especially those of Amun and Ptah. Though his reign was short, his work to restore traditional Egyptian religion helped shape the New Kingdom's future dynasties.

Customize Your Dream Vacation!

Get in touch with our local experts for an unforgettable journey.

Plan Your Trip

The 19th and 20th Dynasties: Power, Glory, and Decline

The New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt reached its peak and began its slow decline during the 19th and 20th Dynasties. Egypt faced its toughest military challenges yet achieved diplomatic successes that would strike a chord through history.

Ramesses II and the Battle of Kadesh

"Ramesses the Great" met the mighty Hittite Empire at Kadesh in 1274 BCE in history's largest chariot battle, with 5,000-6,000 chariots. The pharaoh barely escaped an ambush and led several counterattacks with his personal guard. Egyptian records claimed victory, but today's historians see it as a strategic stalemate where neither side won.

The first peace treaty in history

The fighting lasted 15 years until Ramesses II and Hittite king Hattusili III signed what we now know as the world's oldest peace treaty in 1258 BCE. Silver tablets carried this groundbreaking agreement that spelled out:

- Eternal friendship and lasting peace between Egypt and the Hittite Empire

- Mutual defense against external threats

- Territorial integrity guarantees and extradition of political refugees

- Pledges to solve future disputes peacefully

The United Nations headquarters now displays a replica of this historic treaty.

Ramesses III and the defeat of the Sea Peoples

Ramesses III of the 20th Dynasty faced a life-or-death struggle against the Sea Peoples, who had already destroyed several Mediterranean civilizations. He crushed them in two decisive battles during his eighth year as ruler (c. 1178 BCE). The pharaoh first stopped their land invasion at Djahy in southern Lebanon. He then set up a clever naval trap at the Nile Delta. Egyptian ships blocked the escape route while archers lined the shore. This victory came at a steep price that slowly drained Egypt's wealth.

Economic strain and internal unrest

Egypt struggled with serious money problems by the end of Ramesses III's reign. Workers at Deir el-Medina staged history's first recorded strike in his 29th year because they hadn't received their grain payments. The kingdom suffered from droughts, poor Nile floods, food shortages, and corrupt officials. These environmental problems destroyed grain supplies, hurt trade, and weakened the New Kingdom's foundations.

The rise of the priests of Amun

The priesthood of Amun at Thebes grew stronger as royal power declined. By the late New Kingdom, they owned two-thirds of all temple lands and 90 percent of Egypt's ships. Karnak’s Temple of Amun alone managed 433 orchards, 421,000 livestock, 65 villages, and employed over 81,000 people. The high priests effectively ruled Upper Egypt, making major state decisions through oracles of Amun during the Third Intermediate Period. This dramatic power shift marked the end of Egypt’s greatest era of imperial glory, a story that continues to fascinate travelers exploring ancient sites through Egypt Tours.

The Fall of the New Kingdom and Its Legacy

The New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt started its inevitable decline after Ramesses III's long reign. Its official end came with Ramesses XI's death in 1077 BCE, which led to the Third Intermediate Period marked by political division and weak central authority.

Division of power between Thebes and the Delta

Power split between two centers as the 20th Dynasty ended. The High Priests of Amun ruled from Thebes in Upper Egypt while secular rulers governed from Tanis in the Delta region. This division happened peacefully, unlike earlier intermediate periods. Amun's priesthood had grown incredibly powerful in Thebes, owning two-thirds of all temple lands and 90% of Egypt's ships. The god Amun became Thebes's actual ruler, and priests made state decisions by consulting him through oracles.

Loss of central authority and foreign invasions

Egypt's power continued to fragment throughout the Third Intermediate Period. The country had split into nine major kingdoms by the late 8th century BCE. This political chaos made Egypt vulnerable to outside powers. The Nubians came first and established the 25th Dynasty around 730 BCE. The Assyrians invaded next and brutally sacked Thebes in 663 BCE. The Persians finally conquered Egypt in 525 BCE, ending native rule for the first time in its 2,500-year history.

Cultural and religious influence on later periods

The New Kingdom's cultural legacy survived long past its political collapse. Temple building programs from this era created architectural styles that influenced centuries of construction. Osiris's religious practices dominated almost every temple. Ptolemaic kings validated their power by showing themselves performing traditional pharaonic duties before Egyptian deities, even under foreign rule. Egyptian mummification practices lasted until the seventh century CE—almost two thousand years after the New Kingdom fell.

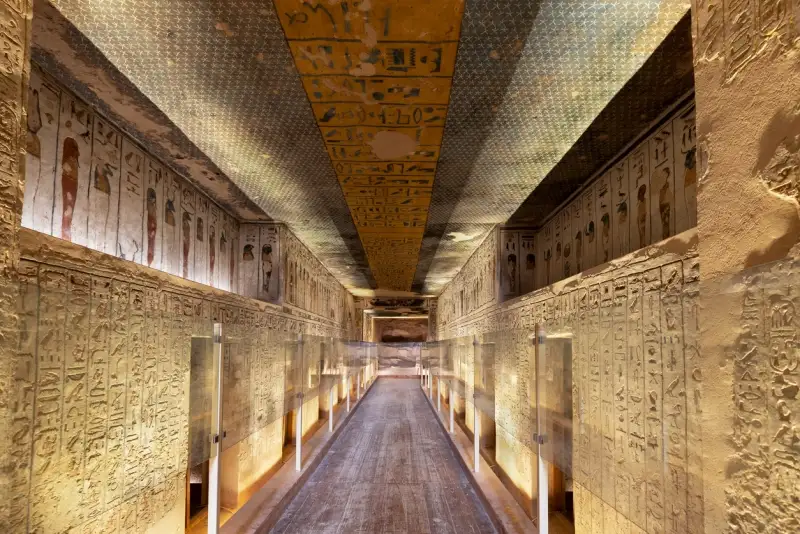

If you’re curious about Egypt’s golden age, the New Kingdom lasted from around 1550 to 1070 BC. When you visit Egypt, you’ll see temples and tombs from this incredible period still standing strong today.

You can explore breathtaking sites like Luxor Temple, Karnak, and the Valley of the Kings, where pharaohs like Tutankhamun were buried. I highly recommend visiting these on your Egypt tour to truly feel the power of ancient civilization.

It’s called that because Egypt expanded its borders farther than ever before. You’ll notice the grandeur in their temples and monuments—it was a time when Egypt ruled much of the ancient world.

You’ll see that art became more detailed and expressive, and temples grew larger than ever. When I walked through Luxor, I could feel how the New Kingdom artists celebrated gods, pharaohs, and life itself in every carving.

Because they’re living history. When you stand before the colossal statues at Abu Simbel or walk through the tombs in Thebes, you’re connecting with stories that have lasted over 3,000 years—something no history book can match.